🚀 Documenting my MSc Dissertation Journey – Part 1

Halfway through my journey as an MSc Occupational Psychology student, I’ve realised that despite the pressure to figure out a career path, an MSc is actually about trying out different flavours of the profession and discovering where you feel most competent and connected with. Lately, I seem to have a growing conviction that I found my ‘sweet spot’—and the MSc thesis was the inspiration to this discovery.

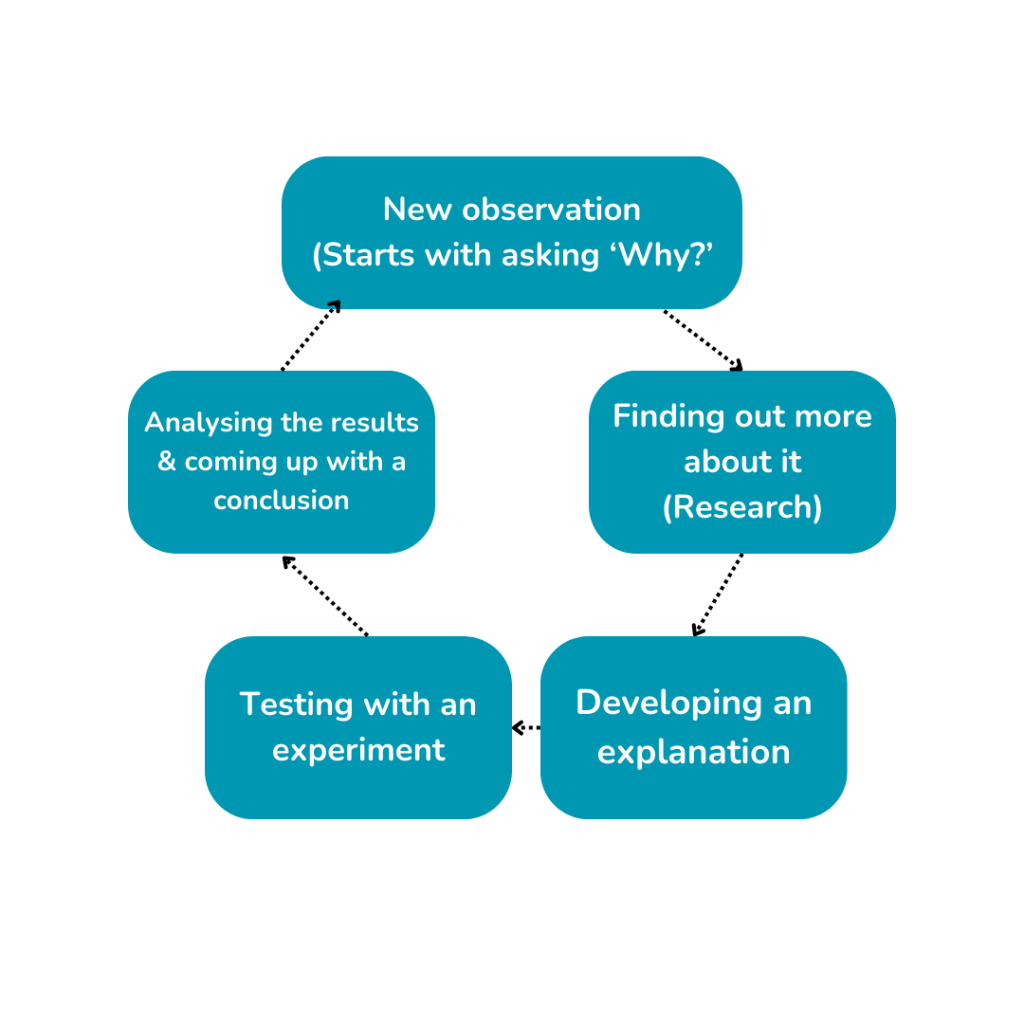

Deciding on a topic for my dissertation was a long and iterative process. At first, I got swept away wanting to explore something ground-breaking; I went down rabbit holes of complex topics and ideas—believing this is where I can do the ‘next best thing’. However, it took a while for me to accept that the ultimate goal of a thesis is not to uncover ground-breaking discoveries (although of course that is entirely possible and amazing!), but showcase your research competence and ability to design and manage a research project effectively. Each step forward contributes to the broader scientific community’s understanding of a particular subject. The thesis is an opportunity to demonstrate your capacity to engage with scholarly literature, formulate research questions, employ appropriate methodologies, analyse data, and draw meaningful conclusions. It’s about the process as much as the outcome, showing that you possess the skills and knowledge to contribute meaningfully to your field.

📌BOUNDARIED CURIOSITY

The process begins with identifying a realistic, time-and-resource feasible, and ethical topic. At this stage, the most important skill is developing curiosity. It’s important to look around you, at things that happen right beside you and think whether you can answer or explore such phenomena through your study. Having a topic that interests you is important to keep yourself motivated, but it is also important to know what you can realistically do within the timeframe that you have. After weeks of discussions with my supervisor, who challenged me to think about the feasibility and relevance of my ideas (while still supporting my ambitious and curious nature), I finally decided to go about things bottom-up. I started reaching out to organisations, hoping that they would have a problem that I, as a researcher, can look into.

📌DEMONSTRATING VALUE

And here’s where I learned another skill—demonstrating ‘value’. It’s not enough to say that you are a student seeking an organisation for their study; it’s crucial to demonstrate the value you can offer the company through your project. This could manifest in various ways, but it’s essential to comprehend the organisation’s primary needs through discussion and dialogue and how your project can align with and address these needs. This approach guarantees a higher probability of success, but fair warning, it won’t always lead to a desirable outcome. It’s important to be prepared to ‘not get what you want’. It’s not a failure—it’s an opportunity to try again, with slight modifications. Although traditionally, universities expect MSc Occupational psychology students to conduct their project with an organisation, there are now several other avenues that can be used to gather participants, like social media. When I was struggling to find an organisation, I decided to switch my approach and develop a research question designed for a population of choice, which I can recruit through these alternate means.

📌CRITICAL READING & PURPOSEFUL NETWORKING

The interest in ‘predictors of resistance to change’ as a topic came about after a conversation with my previous boss. He mentioned how since the pandemic, organisations have made multiple attempts to help their employees integrate with planned and unplanned changes, but they seem to fail because there is an expectancy-value gap between what employers offer and employees need. When I mentioned this to my supervisor, he told me what to do next: “Read”. Focussed and extensive reading is often overlooked, in the hurry to get things in order, yet it’s the most crucial step in the process. Delving into the literature on change highlighted gaps in existing knowledge and revealed where my work could make a meaningful contribution. Ironically, with all the ‘changes’ happening in this profession itself, what better time than now to dive into a topic as relevant as change. The variables for my study emerged through discussions with supervisors, my own research, and conversations with individuals experiencing change first hand.

In conclusion, to develop the right topic for your thesis, it’s important to have four essential skills: boundaried curiosity, demonstrating value, critical reading and purposeful networking. My project is currently underway and still in the iterative stages, but the journey from selecting a topic to narrowing down a research question has also helped me understand my competencies and gauge my interest in a specific field or career path. The process of self-discovery during an MSc should never be underestimated, and every opportunity, such as an MSc thesis, should be maximised for its benefits. And hey! Don’t worry too much about getting things ‘right’—research, by nature isn’t about ‘right’ or ‘wrong’, it’s about discovery, which is what you are and will be doing.