By Madhuri Rajkumar

In the 20th century, in a bustling suburb of metropolitan Chicago, a telephone equipment company – the Western Electric Company – emerged as a monopoly supplier of telecommunication hardware. There was an interesting phenomena being studied at Hawthorne, where their factory was located—the subsequent investigations puzzled the factory owners, academicians, and industry experts.

Now, before I proceed with this story, let me ask you a question.

What, in your opinion, drives your productivity?

Here are some common answers:

- The anticipation of receiving a reward, like a bonus or incentive

- A determination to succeed at something challenging, new or interesting

- A sense of commitment to what you have chosen to do

- The pleasant feeling that arises when being noticed or validated for your work

At Hawthorne, a study was conducted to understand the effects of changing work conditions, like lightning, break times, etc., on the productivity/performance of employees. Somehow, the employees consistently produced high output even when the experimental conditions included longer working hours and shorter breaks. Who would ever feel motivated to perform under these conditions? Would you?

This led to the first and most important question a researcher/scientist/psychologist should ask: ‘Why?’

Children ask ‘Why?’ expecting an epic story to something as mundane as the working of cars or the flowering of a tree. ‘But why?’ they ask, a million times, to the frustration of parents who become the best storytellers in that moment of interrogation. But this small yet powerful word becomes the gateway to valuable information about others/the world and oneself.

Somewhere along the way, however, we outgrew this stage and started accepting close-ended answers to our questions, in the form of rules and facts, often categorised as wrong or right. Conforming to the rules and keeping within bounds meant security and sustenance.

As a psychologist, however, we decide to be anti-conformists. The grey area of not knowing keeps us motivated to test new hypotheses and develop new theories. We regress into the child-like habit of asking ‘Why?’ And the subsequent investigation on why people do things or behave the way they do leads to new insights that make life easier – like what happened in the Hawthorne Studies.

So, what was happening at Hawthorne?

The factory owners at Hawthorne became interested in this productivity phenomena and they wanted to use whatever was happening there to improve productivity of all their employees. So, they called in the big guns — academicians like Elton Mayo, who insisted on understanding the behavioural and psychological reasons behind productivity. His deep dive into this aspect of motivation developed some turning-point answers in management studies. It became evident that people want to be noticed, attended to and cared for. They want to be involved and regarded, rewarded and understood. If this discovery didn’t happen, we would have been ages behind in understanding employee motivation and consequently developing effective management techniques. So, cheers to Elton, the other investigators and the factory owners who didn’t stop asking ‘Why?’

“When curiosity turns to serious matters,

it’s called research.”

– Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach

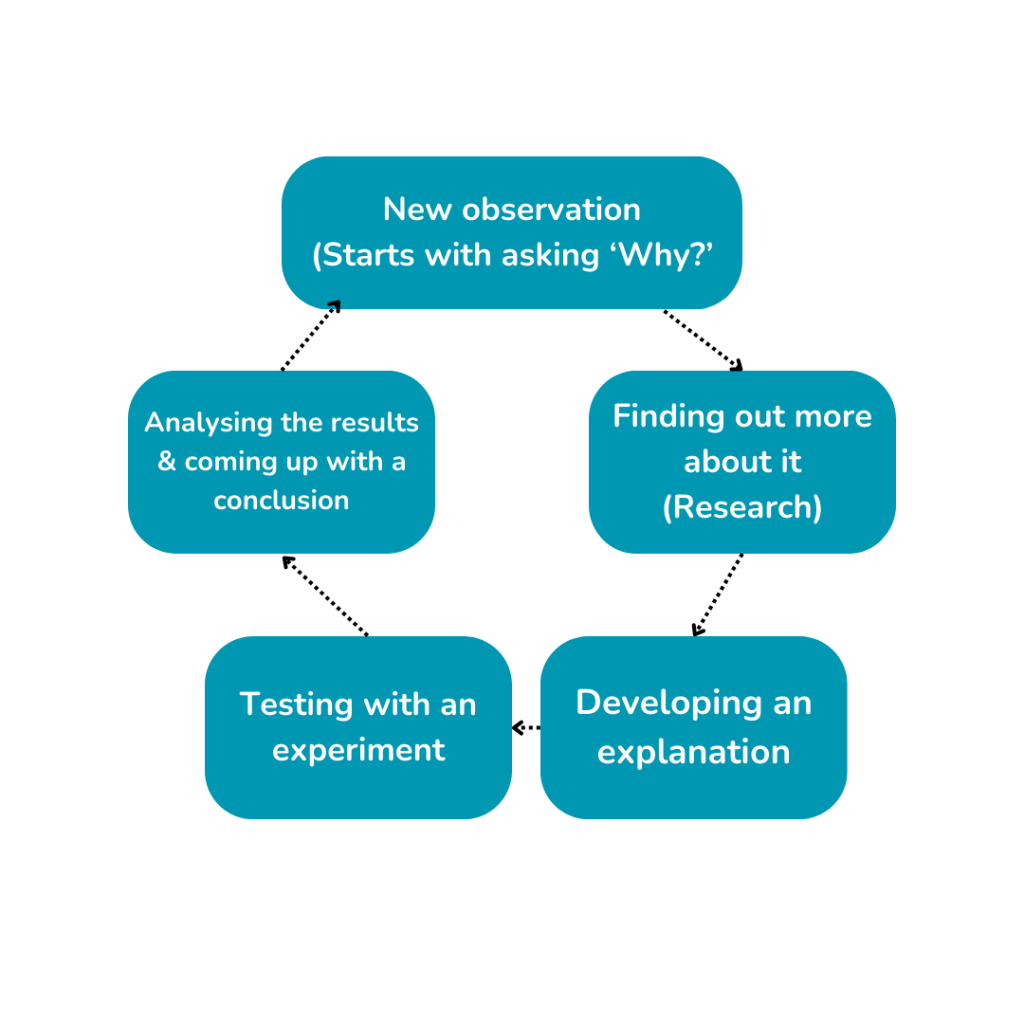

Every day we make observations. We make observations about the people around us, our surroundings, and if self-reflective enough, about ourselves. Out of these, even if we choose to ignore some, something else might keep us awake, wondering ‘Why?’ And there begins your scientific journey to establish lines of evidence to either credit or discredit these observations. Once you’ve arrived at satisfactory conclusions, you apply them to real life and test the outcomes. It doesn’t stop there. You test and re-test, keeping in mind that there is no right or wrong, only a series of developments to how things were vs how things can be.

So, fellow psychologists, here are some takeaway messages, not only from enterprising studies like the Hawthorne Experiments, but as observed from instances of daily life:

- Be constantly and forever intellectually curious

- Do not limit yourself to a single answer; yearn to know more

- Finding evidence to prove yourself wrong is also as valuable as evidence to prove yourself right (A good observation/study is always falsifiable)

- Use your curiosity for the good of others, with a determination to make their lives better or easier

Elton Mayo and his fellow researchers played a role in inspiring a culture of active listening, empathy and interpersonal support in the Western Electric Company, positively influencing many workers’ lives – all because they couldn’t stop thinking about why people kept working under poor lighting.

Here’s a link to read more about the Hawthorne Experiments, the ‘Hawthorne Effect’, and its various implications: https://www.bl.uk/people/elton-mayo. We’ll also talk about Evidence-based Practice (in later blogs), which is the standard in Occupational Psychology (briefly mentioned through the diagram above). And once inspired,

Take a look at the world around you, your work or academic space and think of where you may have missed out on asking the big question: ‘Why?’